“More Korean seniors are stepping up to donate their bodies to science”

When it seemed her time was near, Hyun Choi summoned her six children to Southern California — four of them from South Korea.

Her last wish, Choi told them as they sat in her Fullerton home, was that she wanted to donate her body to science.

Her children were appalled. Her decision struck them as flying in the face of Korean customs. They wanted to be able to visit her at the burial plot they had set aside in Korea, next to where their father lay.

But Choi was adamant. She’d heard on the radio that body donations were far lower among Asians than other races, and believed that she and other Korean Americans should do their part to further medical research.

One by one her children relented.

When Choi died in 2008, at 84, her body went to the University of California, Irvine. An official told her daughter Amy Kim that Choi was one of few Asians to make such a gift — in the previous seven years, just four Asians had donated to UCI’s willed body program.

Since then, in part because of Choi’s decision, a movement has begun among Korean immigrants in Los Angeles to change their community’s perspective on death.

“I’m so thankful in hindsight,” Kim said. “It was like she was the giving tree.”

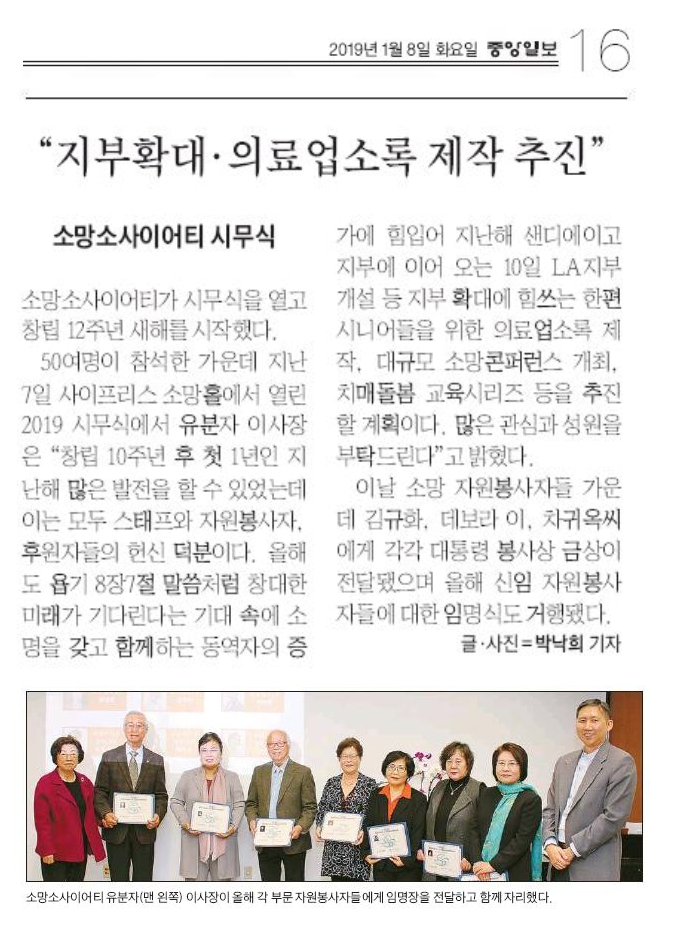

Spurred partly by Choi’s story, a Cerritos-based group called Somang Society began urging Korean seniors to donate their bodies to medical research. Since 2009, 32 have donated through the campaign, and nearly 900 more have pledged to do so.

The campaign has been “a game changer” in attitudes about scientific donation among Korean Americans, Tom Vasich, a spokesman for UCI, wrote in an email.

Heading the campaign is 80-year-old Boon-ja Lee, who started the organization to encourage Korean Americans to talk about the culturally taboo subject of death and dying.

Like other Asians, many Koreans avoid the number 4, which is read the same way as the Chinese character for death.

“We just don’t like the thought of death,” Lee said.

Many of her contemporaries — “old-timers,” as the first wave of immigrants to settle in Koreatown are known — would shush her when she brought up the topic, saying it was inauspicious because speaking of it would make it reality.

Her husband of five decades was reluctant to discuss dying to his final days, and her adult son still cringes and objects when she brings it up, she said.

But after she retired in 2006, and facing her own mortality, Lee began thinking differently about various aspects of death and dying. After she heard Choi’s story, she pledged to donate her own body and began urging others to do the same.

She also found herself thinking back to something she’d seen often in her career as a registered nurse: brain-dead seniors kept alive on machines for years. Wanting no part of that, Lee wrote out an advance health care directive for herself, asking not to be resuscitated or kept alive with tubes.

Then she started holding seminars and lectures urging other Korean American seniors to do the same. She has now spoken at about 150 seminars at churches and community centers, at which more than 10,000 have written out healthcare directives, she said.

“I tell them we should face death rather than let it happen to us,” she said. “A lot of us prepare more for trips than we do for death.”

One pastor was resistant to her entreaties, Lee said. Then one day, out of the blue, he called Somang Society’s offices saying he wanted a health care directive. He and his wife signed one on a Thursday; that Saturday morning he had a heart attack and ended up brain-dead, Lee said.

Attitudes are also changing about body donations, says Chang Sok So, a physician and unpaid consultant for UCI’s willed body program, who for 18 years taught anatomy courses to practitioners of Eastern medicine in Orange County.

Statistics on the racial breakdown of whole-body donations are not readily available, in part because donations are anonymous. But So says his students used about 40 bodies annually, and for years he never saw an Asian cadaver.

By the time he retired late last year, Asian American bodies were becoming more available.

As for Choi’s six children, four have signed up to donate their bodies to science, Amy Kim said.

Kim, 60, said she thought her mother’s wishes ultimately came full circle.

Not long after Choi’s death, two of her grandchildren entered medical school. They may have the previously unlikely opportunity to learn about preserving life by studying the bodies of Korean Americans.

By Victoria Kim Contact Reporter

![2016년 1월 31일 [로스엔젤레스 타임즈]](https://kr.somangsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/la-la-me-korean-death-campaign-jpg-20160130.jpg)